Implementing Ethics in Autonomous Vehicles

Author: Lau Johansson

1st August 2020

Reading time: 15 min.

Introduction

A car drives down the road. A group of five people walks out in front of the car. The car can save the five people’s lives by steering the car onto the sidewalk – but this will kill a pedestrian.

What should the car do? Save the five people on the road or the pedestrian?

Tesla’s CEO, Elon Musk, announced in July 2020 that the cars are close to reaching level 5 autonomous cars (full self-driving). Autonomous vehicles (AVs) have the potential to create more effective traffic, reduce emissions, and eliminate up to 90% of accidents in traffic. Self-driving cars also entail new challenges related to system failures, politics, and regulations. In the future, self-driving cars might be driving among all of us in the traffic. The AVs will in unavoidable accidents be forced to make moral decisions. It is therefore important to discuss ethics related to self-driving cars.

What to expect of this post

This post sheds light on the importance of ethics in Artificial Intelligence (AI) – especially autonomous vehicles. It contributes to the understanding of how ethical principles can be implemented in self-driving cars. The findings and methods proposed can, in my opinion, be used not only related to AVs but in all areas of AI.

This blogpost is structured in the following way:

- Introduction to AVs

- Introduction to ethics

- How to formalize ethics mathematically (For the interested reader)

- An accident scenario

- Reflections emphasizing challenges regarding ethics and AVs

Machine learning and AV's

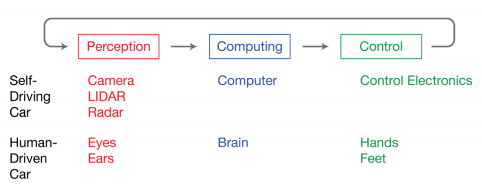

Autonomous (driverless) cars are vehicles, which fully or partly can drive without assistance from a human driver. Decision making and actions performed by the autonomous car can be divided into three parts: Perception, thinking (computing) and acting (control). These stages are all necessary for replacing human drivers.

Picture from: http://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2017/self-driving-cars-technology-risks-possibilities/</figcaption>

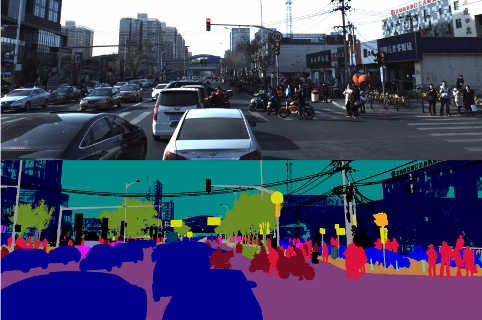

How does this relate to machine learning? The data from the cameras, LIDARs, and radars are passed to a computer inside the car. To let the car “see” its surroundings convolutional neural network decides WHAT objects there are on the road (e.g pedestrians) and WHERE the object is located. This is respectively called “Image Classification” and “Image localization”.

Picture from: https://autonomous-driving.org/2018/07/15/semantic-segmentation-datasets-for-urban-driving-scenes/>

Why ethics?

Implementing autonomous cars will mean that it is no longer humans who have to make decisions in the traffic. This technology evolution potentially implies concerns about how cars make moral decisions. One of the most challenging tasks related to artificial intelligence is to create ethical autonomous machines. The cars will interact with humans in traffic; thus a major responsibility lies in the programmers of the cars. Engineering ethics is important because the focus on ethical aspects in technology (including machine learning) contributes to a more safe and applicable technology. Moreover, incorporating engineering ethics in machine learning projects will improve the engineers' ability to manage moral questions.

This post examines, how autonomous cars should act in traffic. Ethics appears in relation to ethical dilemmas, which are situations, where it is unclear how we should act. Autonomous cars will be involved in ethical dilemmas where moral decisions have to be made – decisions about life and death.

The Trolley Problem

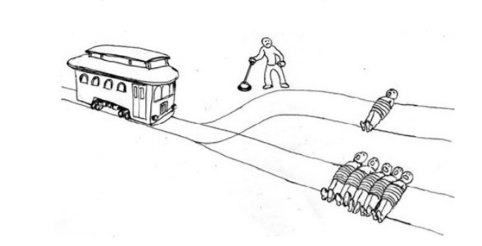

An often used moral decision dilemma is the “Trolley Problem”. The origin of the dilemma is a thought experiment made by Phillippa Foot and has been re-written in many ways. I have formulated it so it matches the illustration.

“A man controls a switch of a runaway tram which he can only steer from one narrow track on to another. Five men are lying on one track and one man on the other. Anyone on the track the train enters is killed”.

Picture from: https://newrepub-lic.com/article/139161/trolley-problem-explains-2016

Some people would say, that if the man with the control switch does not do anything – he actually does not kill them – he just “let them die”. Even though this seems a little harsh – are they right?

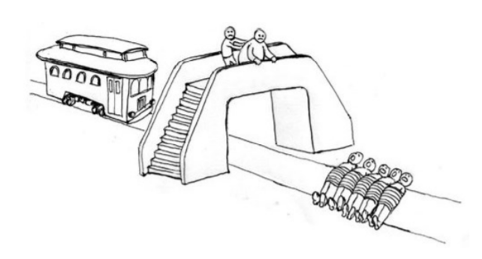

The experiment has later been extended by J. J. Thomson and goes as follows (this is more or less directly cited by Thomson):

“George stands on a footbridge over the trolley tracks. He sees a trolley out of control. On the back of the bridge, there are five people. The people can not get away in time. George knows, that the only way to stop the trolley is to drop a very heavy weight on its path. The only available, sufficiently heavy weight is a fat man, who also stand on the footbridge. George can push the man down on the tracks and kill the fat man. Or, he can refrain, but then the five people die”.

Picture from: https://newrepub-lic.com/article/139161/trolley-problem-explains-2016

How would you decide? Try out different scenarios at https://moralmachine.mit.edu/

Three ethical theories

Several ethical theories put a focus on how to approach ethical dilemmas. Three theories will be presented in this post: Utilitarianism, duty ethics, and rights ethics.

Utilitarianism

From a utilitarian point of view, one should always behave, such that the action always maximizes the welfare for as many people as possible. Utilitarianism is a consequentialist theory, which means that moral correctness of an action only depends on its consequences. There exist some disagreement between utilitarians about what a “good” consequence is. According to hedonism, “pleasure” is the only intrinsic good and “pain” is the only intrinsic bad.

Duty ethics

Contrary to utilitarianism, duty ethics is non-consequentialistic. It means, that in relation to moral correctness of an action this theory emphasizes the action itself (the motivation of the action) instead of the consequences.

Philosopher, Immanuel Kant, formulated the so-called “second imperative”. This imperative is a way of describing our moral duties. It goes as follows: Act so you treat humanity, whether your own person or in that another, always as an end and never as a means only. This formulation is the foundation of an ethical theory called deontology. In this post, it is assumed that duty ethics is the same as deontology.

Rights ethics

In my opinion, rights ethics can be difficult to wrap one's head around – so don’t be too frustrated if it doesn’t make sense the first time.

Rights ethics is also non-consequantialistic. Rights ethics focus on moral rights – a subclass of these rights is natural rights. Natural rights are rights that humans have because of their nature. Natural rights are e.g rights to life and rights to liberty. A theory (status-based theory) explains why these fundamental rights should be respected: Because we humans have some properties from nature – it gives us rights.

Rights can be looked at using the Hohfeldian System. The Hohfeldian system breaks rights into four basis rights (called Hohfeldian incidents): privileges, claims, power, and immunity. Each of them has its own logical form and together they define complex “molecular rights”. Read this page for more.

Ethics and risk

To be able to implement ethics in AVs as proposed in this post, one must be able to quantify risk. This quantification is not an easy task. Some could say that risk is a product of the harm of an accident multiplied by the probability of the event happening. But using probability-theory in AV’s machine learning algorithms is a challenge. First, it requires an in-depth analysis of a huge amount of data. Secondly, the process of validating the results is NOT “right up our street”.

In this post, risk is related to the safety of humans. It is assumed that safety is related to physical safety – specifically the bodily safety related to life and death.

Proposing three mathematical formalizations

In this post, mathematical logic is used to formalize the three ethical theories. Mathematical modeling is a work process where mathematics is applied to shed light on problems from the real world. If you are interested in a brief introduction to how to work with mathematical logic and ethics – Link - this blogpost is for you.

How the theories could work out in real life

Accident scenario

An autonomous vehicle drives with a person, person A.

Five persons, B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5 stand in the middle of the road.

They will be killed if the car hits them

Another autonomous vehicle is parked, inside is person C.

The car, where person C sits, can drive out in front of person A’s car. This will save the five persons on the road. But, unfortunately, kill person C.

Option 1: Person C stay parked.

Option 2: Person C drives out in front of Person A.

The moral decision must be made by Person C’s autonomous car.

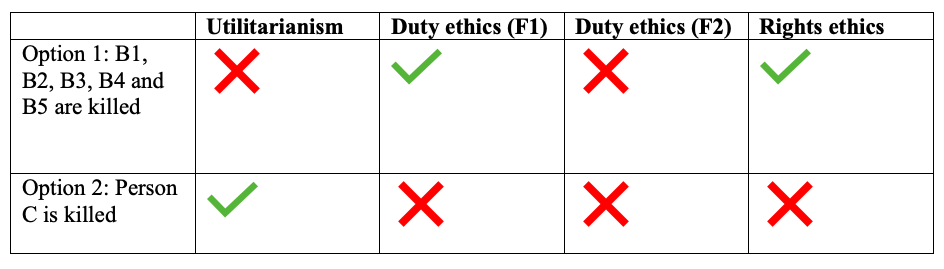

Moral "correct" decisions of the accident scenario

Please keep in mind, that the following conclusions are based on mathematical formalization made by the author of this post. The conclusions are therefore conditioned by the underlying assumptions.

Decisions can either be:

Here is my take on how each of the theories conclude on the scenario:

Hopefully, it is clear for you as a reader, that a utilitarian would prefer to kill person C instead of B1, B2, B3, B4 and, B5. By killing five people instead of one - the risk has been decreased for as many people as possible - said in another way; the "welfare" has been maximized for as many as possible.

What is interesting to see is the conclusion of duty ethics (F1). It is morally incorrect to choose to kill Person C and thereby save B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5. This scenario then shows, that according to Kant, it is morally incorrect to use YOURSELF as only a means to an end.

Using the formalized version of rights ethics, it is morally correct to kill B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5. An important assumption is that it is B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5 own fault, that they are at risk of getting killed. If this assumption was not made, rights ethics would have concluded the decision as morally incorrect.

One could question whether it is true, from a rights ethics perspective, that it is morally incorrect to kill person C. If rights ethics assumes that a person is free and independent, then it must be “allowed” to choose to kill yourself to save another person. But…. Will this interfere with B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5 rights to stand on the road with the risk of getting killed? Wow… this can get complex to analyze! I will not dig any deeper into this.

Reflections

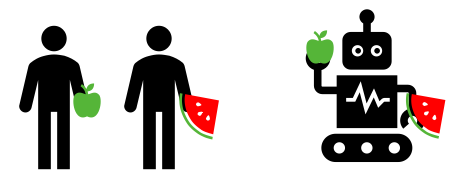

Math vs. human language

Mathematics is a great tool for translating human language so that computers can understand it. Though, the implementation of formalized ethics is limited by a lot of assumptions. Changing one assumption can change the outcome of a decision completely. Moreover, mathematical logic is often more “strict” than human language. If someone says to you: “You can either take an apple or a piece of watermelon”. I bet you would think you could take either an apple or a piece of watermelon. But, could someone might think that it is OK to take both? A robot would actually think that it is allowed to take both the fruits. These ambiguities in human language is a major challenge when “translating” human language to AVs.

In the context of ethics and AVs, the fruits could represent human lives. The robot could be an AV.

Moral preferences

Opinions on ethics are also not unambiguous. A study with 1900 participants has been conducted, to find out which moral algorithms the population of the society is willing to accept. The conclusion was, that participants tend to agree that everyone will be in the best position if self-driving cars are utilitarian. The very same participants have a personal incentive to drive in self-driving cars that protect themselves at all costs. In other words, we want others to drive cars which do the “best” for all of us. But, the car we drive ourselves must prioritize our own lives. Read the article here.

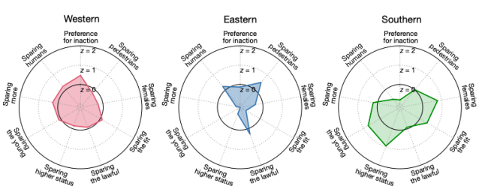

Moral preferences can vary cross-culturally and the study "The Moral Machine" has identified three distinct clusters of countries with common moral preferences. It turns out to be great differences between the clusters, where, for example, in “southern countries” there are strong preferences, that the lives of young people as well as the lives of women must be saved, but in return have lower preferences about saving humans over animals.

In my opinion, political regulation is a challenge in relationships for the introduction of self-driving cars and by implementing ethics in self-driving cars, the study “The Moral Machine ” is relevant, as politicians should be aware of moral preferences in the countries where self-driving cars are to be implemented. Read the article here.

Reflection of the author

In the last part of this blog post, I’ll emphasize how many questions arise in the implementation of ethics into AV’s.

Which ethics should be implemented?

Even if (when) some can implement fully working and validated ethics into AVs – which ethics should be chosen? Choosing among some of the traditional ethical theories – there is still ambiguity in what decision is morally correct. The moral preferences even differ between cultures. Already now, you have might found it hard to decide which of the decisions in this blog post is the most morally correct. How can we implement ethics in AV’s if we (humans) cannot decide what a morally correct decision is?

Who has the responsibility?

Another challenge regarding ethics and AVs is the distribution of responsibility? If (when) ethics can be implemented into AV’s the machine learning algorithms have been developed by a programmer. The software using the ML algorithms are integrated into the cars by the car manufacturers. The car has been bought by a person who chooses to use it on the roads. If the AV ends up in an accident and kills a person – who has the responsibility? The programmer? The manufacturer? The car owner? Can the car itself be responsible for the kill?

If we need ethical regulations on AV’s – why don’t human drivers need anyone?

Most of us can possibly agree that ethics should be incorporated when implementing AVs. The decision of the driverless car has to make decisions that correspond to what humans believe to be morally correct. To my knowledge, human drivers do not have to consider any ethical aspects of being the driver of a car. Not during driver education course nor after. If AV’s needs ethical regulations – why don’t human drivers need any? How should you, as a driver, choose among lives in the traffic? Today, decisions in traffic depend on individual driver’s ethical belief and immediate reaction in an accident.

Reading this blog post might make you consider your ethical beliefs. Are you even able to make the right decision when you only have a few seconds to decide?

As a side note, the average reaction time for a human driver is 1.6 seconds. AV’s equipped with radar/LIDAR and camera have a reaction time of 0.5 seconds. At the moment, a camera radar module is being developed. This will make the AV being able to react in only 10 milliseconds – 160 times faster than a human driver.

A thought experiment

Working with implementing ethics in technology also puts focus on how humans interact with technology. Among some of the challenges with ethics and AVs are: ambiguities in ethical theories, different moral preferences between individuals and cultures as well as the distribution of responsibility.

Trying to embrace these challenges I have tried to construct a thought experiment. It goes as follows:

What if all AV’s are equipped with three buttons – each of them representing an ethical theory for the AV to respond to? When the passengers of AVs get into the car they must choose one of the buttons.

Could this be a step closer to implementing ethics in autonomous vehicles?

Thanks for reading the post!

Links

The content of this post is mainly based on the bachelor thesis by Lau Johansson. It unfortunately only exists in a danish version.